JESSICA IS SURPRISED BY HER GREAT-GREAT GRANDMA SERAPHINA PEARL.

- Avery Navarro

- Feb 13, 2025

- 2 min read

Seraphina's grand daughter, my grandma, was sitting on our veranda on a pile of silver aluminium cases. The largest case the base, the middle two set for elevation, and the smallest her seat. Her presence was memorable, hair abundant and white, cut in a bob fashionable in the 1960s, red cats eye sunglasses, a Mary Quant black mini skirt, with a square white collar and white cuffs, and red white and black tights with horizontal striped tights spinning down shapely legs into leather ankle boots. She was staring out at the harbour smoking an Indonesian clove cigarette, glancing occasionally at a leather-bound folder in her right hand.

“Grandma?” I asked, surprised at the quaver in my voice.

She turned and peered at me through her red cat’s eyes.

“Sorry?” She asked, tapping her cigarette to dislodge some ash.

“Grandma it’s me, Jessica.”

She sighed with relief.

“Jessica, well that’s good. I’m sorry to be cluttering the veranda dear, but I can’t find my bloody door key.”

She took a final drag of her cigarette and threw the butt into the garden.

“That’s okay Grandma, it has been forty years.”

“Never mind. Well, come up and let me get a decent look at you,” she said, taking off her sunglasses. “You have the family good looks I see, thanks to useful deoxyribonucleic acid from a long line of attractive grandmothers.”

It was seven-thirty am, and this particular attractive grandmother, as improbable as my mum had predicted, was coming at me at a discomforting speed. I closed my mouth, which was embarrassing, because it must have been open.

“Come on dear, get up here and give your long-lost grandma a kiss.”

When I finally got hold of her, I found a sturdy body moving with fluid ease. She was definitely no little old lady. Her perfume was strong and familiar.

“Este Lauder White Linen,” she told me later, “goes with Quant’s linen trim.”

After a strong squeeze she pushed me back at arm’s length and examined me. Her eyes were an unusual cobalt blue, almost otherworldly.

“Bloody hell,” she said, staring at me, “I really can’t believe it.”

“Sorry?”

“Here,” she said, handing me the leather-bound folder, “take a look at this and tell me what you see.”

I opened the cover. It was a black and white studio portrait of a woman in the 1920s. She was about my age, with short dark hair cut almost like my own. I was looking at an unfamiliar version of myself, someone similar but not the same, like a non-identical twin sister, and the harder I stared, the more I felt the eerie sense of collapsed time.

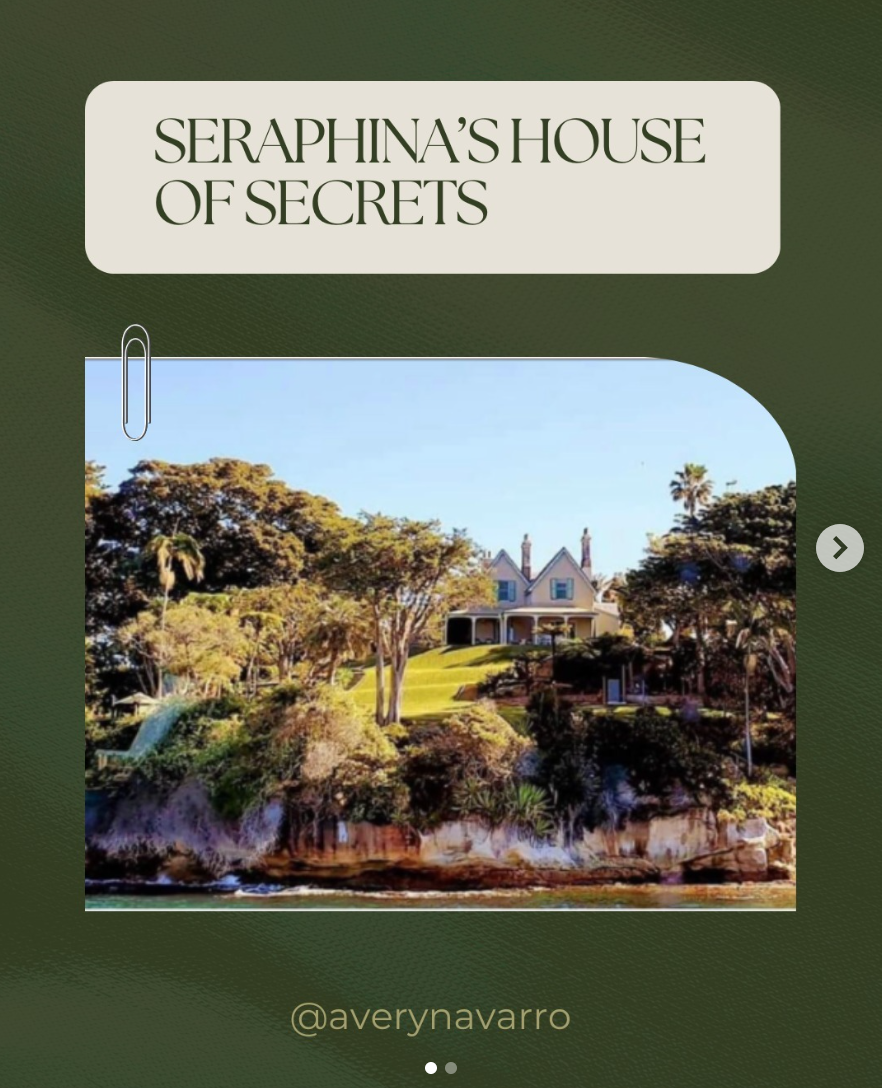

“Seraphina Pearl,” said, Grandma, “the woman who built this place in 1920. I had this with me for purely sentimental reasons. I didn’t expect her to walk out from behind a bougainvillea bush a hundred years later.”

“Incredible,” I said, staring at my doppelganger. “This is so strange.”

“Not as strange as you think my dear, have a poke around on Google. You’ll see it happens often.”

“I had no idea.”

“Nor did I, until you stuck your head out of the bougainvillea. What it means, we’ll just have to see.”

Comments